The United Nations Calls for a Comprehensive Review of Egypt’s Draft Criminal Procedure Law to Ensure Compliance with Human Rights Standards

The United Nations Special Rapporteurs on Human Rights have submitted a joint memorandum to the Egyptian government regarding the new draft Criminal Procedure Law, as the House of Representatives continues its discussion of the contentious provisions within the proposed legislation. Below, the Arab Center for Law and Society Studies provides a summary of the key points raised in the memorandum:

- Pretrial Detention

The new draft law reduces the maximum duration of pretrial detention for misdemeanours from six months to four months, for felonies from 18 months to 12 months, and for felonies punishable by life imprisonment or the death penalty from 24 months to 18 months. However, the maximum duration of pretrial detention in cases of appeals against life imprisonment or death sentences remains 24 months.

While the reduction of these periods is welcomed, they remain lengthy and continue to allow for extended pretrial detention, which contradicts Article 9(3) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, stipulating that pretrial detention must be an exception and for the shortest time possible.

The Human Rights Committee emphasized the need for individualized decisions regarding pretrial detention, based on logical and necessary justifications, such as preventing the accused from fleeing, tampering with evidence, or repeating the offence. The Committee further stressed that prolonged pretrial detention without judicial review undermines the presumption of innocence, a cornerstone of human rights protection that ensures no individual is presumed guilty until proven otherwise.

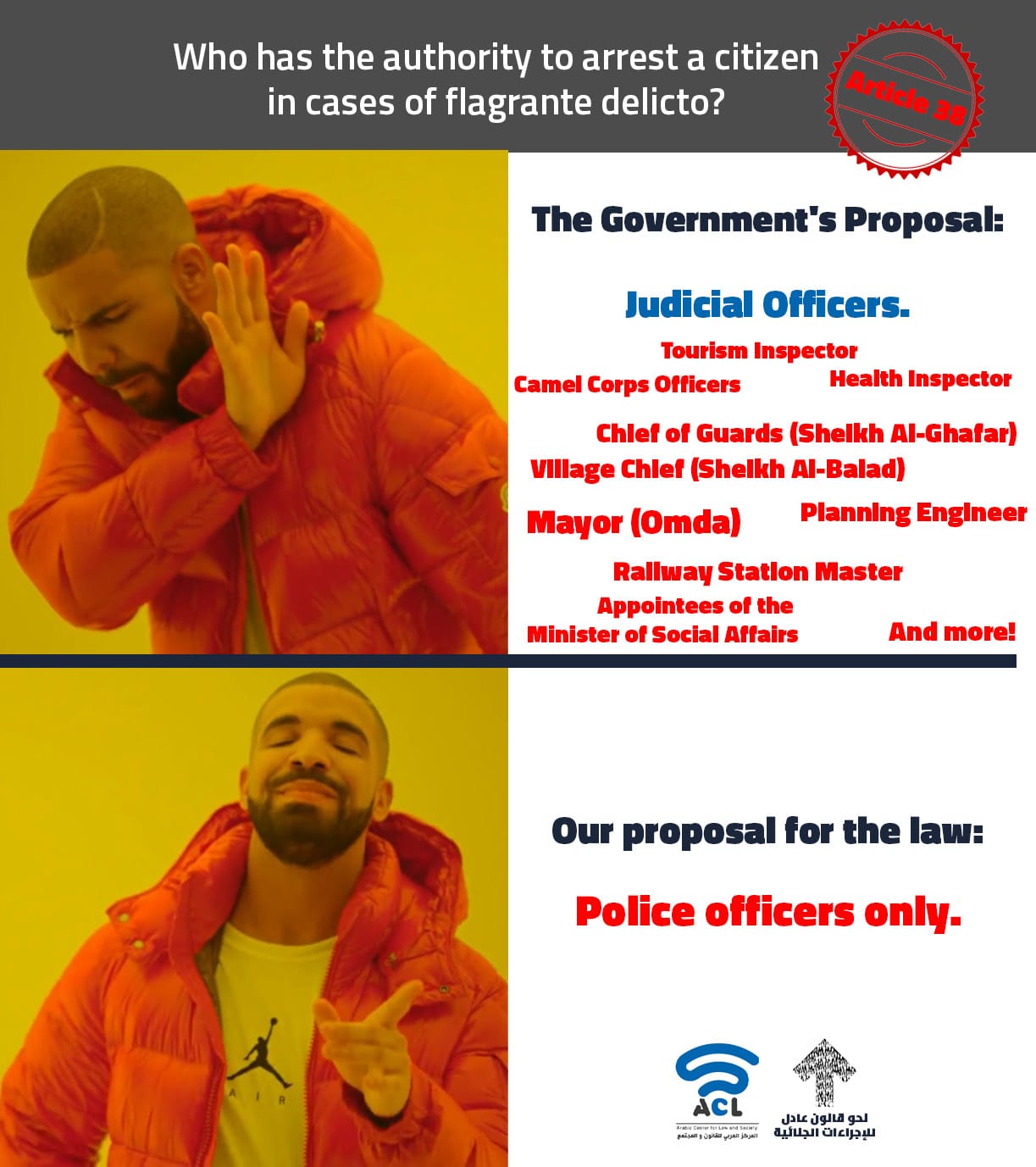

- Expansion of Prosecution Authorities

The proposed draft law grants the Public Prosecution extensive powers, including the ability to renew pretrial detention for up to 150 days for certain crimes without judicial oversight, such as offences related to national security, terrorism, and spreading false information. These broad charges could be used to target opposition figures, journalists, and human rights activists, raising significant concerns about human rights violations.

The draft law also allows the Public Prosecution to impose pretrial detention for up to four days before presenting the accused to a judge, violating the right to prompt judicial review under Article 9(3) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which requires that pretrial detention be an exceptional measure based on necessity and proportionality.

Furthermore, the law grants the Public Prosecution additional powers, such as issuing travel bans and freezing assets without a clear time limit. This contravenes Article 62 of the Egyptian Constitution, which stipulates that such measures must be time-bound and justified. These expanded powers facilitate the arbitrary use of punitive measures against critical voices, impacting individuals’ economic and social rights.

The proposed draft law also grants the Public Prosecution broad powers to intercept communications and monitor social media platforms, posing a significant threat to the right to privacy and freedom of expression. This is particularly concerning given the lack of sufficient procedural safeguards and effective judicial oversight.

Although the law includes provisions for compensation for unlawful pretrial detention, the strict conditions for obtaining such compensation undermine its effectiveness, especially for victims of prolonged detention or the practice of "recycling" cases.

These amendments violate international standards that emphasize the necessity of separating prosecutorial and judicial functions and ensuring effective and prompt judicial oversight of detention. They also facilitate human rights violations, underscoring the urgent need for a comprehensive review to ensure compliance with constitutional rights and international standards.

- Remote Judicial Procedures

The proposed draft law allows pretrial and trial sessions to be conducted remotely via video conferencing at the discretion of prosecutors and judges. This includes investigative sessions, interrogations, and even the trial of minors. While it is possible to appeal the decision for remote trials, the appeal is submitted to the same court that issued the decision. Additionally, Article 529 removes the requirement for defendants, witnesses, experts, and interpreters to sign session records, limiting signatures to judges, prosecutors, and court clerks.

These amendments raise serious concerns about violations of human rights as stipulated in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), particularly regarding the right to a fair trial, protection from torture and ill-treatment, and the right of detainees to appear in person before judges. Personal presence is essential to ensure investigation into detention conditions and effective defence.

Remote trials could also create practical barriers, such as poor connectivity, which may hinder lawyers' ability to represent their clients effectively and communicate with them in private. Reports have indicated that judges sometimes prevent detainees from speaking freely during remote sessions, citing time constraints and a high volume of cases, thereby compromising fair trial guarantees.

Remote trial sessions should only take place with the explicit consent of the accused and under conditions that guarantee a fair trial, including effective access to legal counsel. Failing to uphold these safeguards exposes defendants to violations of their rights to defence and judicial accountability against torture, exacerbating limitations on procedural justice.

- The Right to Defense and a Fair Trial

The proposed draft law grants the Public Prosecution extensive powers that negatively impact the right to a fair trial. Article 69 allows investigations to be conducted in the absence of the defendant’s lawyer if deemed necessary by the prosecution, enabling the interrogation of detainees without legal representation. This constitutes a violation of the right to defence as stipulated in Article 14 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). Furthermore, the draft law does not provide guarantees to ensure that defendants have access to legal counsel during interrogations or opportunities to consult with them privately, undermining procedural justice.

Articles 73 and 105 grant the prosecution the authority to restrict lawyers’ access to case files under the pretext of "investigative interests," hindering the defence of the accused. Article 72 allows the prosecution to limit lawyers’ ability to speak or object during interrogation sessions, resulting in an imbalance in the means of defence available to the parties.

The draft law also expands restrictions on the right of defendants and their lawyers to cross-examine prosecution witnesses. This includes relying on witness statements recorded in police reports without requiring their appearance in court. Additionally, the law grants judges broad powers to deny requests to summon witnesses for either the defence or the prosecution. These restrictions violate the right to confront evidence under Article 14(3) of the ICCPR, weakening the principle of equality in the means of defence.

The broad empowerment of the prosecution to restrict defence rights, coupled with the absence of sufficient procedural safeguards, directly threatens fair trial guarantees and undermines the principles of justice and equality before the courts.

- Public Trial Sessions

Articles 266 and 267 of the draft law expand restrictions on disseminating information about court sessions. Article 266 prohibits the recording or broadcasting of court proceedings without written approval from the presiding judge, while Article 267 criminalizes the publication or discussion of trial details, particularly those related to the Anti-Terrorism Law, under the pretext of protecting the "proper administration of justice." These restrictions conflict with the constitutional principle enshrined in Article 187 of the Egyptian Constitution, which guarantees public trials, and contradict international standards ensuring the right to public and fair hearings under Article 14 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

Restricting the reporting of trial proceedings and the dissemination of information, in general, hinders public access to matters of public interest and limits freedom of expression, including the right to criticize judicial processes and the performance of judges and prosecutors. Such amendments may deter lawyers, journalists, and human rights defenders from writing or reporting on cases due to fear of punitive actions, fostering a climate of self-censorship and weakening judicial transparency and accountability.

The proposed restrictions are inconsistent with Article 6(a) of the Declaration on the Right and Responsibility of Individuals to Promote and Protect Human Rights, which guarantees the right to access information related to fundamental rights and freedoms. Additionally, Article 9(3)(b) of the Declaration ensures the right to attend public sessions to assess their compliance with national laws and international standards.

These amendments reflect a trend toward curbing freedom of expression and information-sharing, harming the right to a fair trial and undermining transparency within the judicial system. To ensure the protection of rights, public trial sessions must remain the default, with any exceptions being limited and justified in accordance with constitutional and international standards.

- Safeguards and Accountability

The proposed draft law imposes severe restrictions on holding state officials accountable for potential violations. Article 226 prohibits filing civil lawsuits against state officials for actions committed during their duties, while Article 162 limits victims' rights to challenge prosecution decisions to close cases against these officials or to file independent civil suits, leaving investigations and legal proceedings solely under the authority of the Public Prosecution.

These amendments undermine victims’ rights to justice and accountability, particularly in cases of enforced disappearance, torture, and other human rights violations. They violate Egypt’s obligations under Article 13 of the Convention Against Torture and Article 2 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which guarantee victims the right to redress and effective remedies for violations. They also contradict the UN Declaration on the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, which emphasizes the protection of victims and witnesses and ensures the accountability of perpetrators.

Article 42 of the current Criminal Procedure Law, which will remain largely unchanged under Article 44 of the proposed draft, grants prosecutors and judges discretionary authority to oversee detention centres without a legal obligation to do so. This raises concerns about effective oversight and prevention of violations within detention facilities.

Additionally, the ambiguity in counterterrorism laws, combined with the proposed amendments, increases the risks of violations of fundamental human rights. Restrictions on disclosing information about judges, prosecutors, witnesses, and defendants in terrorism-related cases foster a climate of secrecy and reduce transparency, heightening the likelihood of arbitrary application of these laws.

The amendments pose significant risks to fundamental freedoms, as well as to human rights defenders, lawyers, and journalists, potentially undermining the rule of law and escalating rights violations under the pretext of counterterrorism. To ensure the protection of rights and uphold the rule of law, these amendments must be reviewed in line with international standards and Egypt’s legal obligations.

In light of the above considerations, the memorandum requested the Egyptian government to conduct an independent and comprehensive review of the draft law to ensure its compliance with Egypt's international human rights obligations. This should include consultations with experts and civil society. Additionally, the memorandum sought the government’s response on the following issues:

- Please provide any additional information and/or comments you may have regarding the above analysis.

- Please clarify the extent to which the aforementioned amendments to Criminal Procedure Law No. 150 of 1950 align with Egypt's international obligations, particularly with the principles and standards related to protection from arbitrary deprivation of liberty, the right to due process, and guarantees of a fair trial as stipulated in international human rights instruments, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

- Please provide details regarding any measures taken by your Excellency's government to prevent the arbitrary use of pretrial detention, including the practice of “recycling,” where the prosecution adds detainees already held on current cases to new cases with similar charges to keep them in indefinite detention. Additionally, please clarify how your government ensures that pretrial detention is not used as a tool against critical voices or as a means of suppressing legitimate and peaceful opposition.

- Please explain how the expansion of prosecutorial powers aligns with Egypt's international obligations and human rights standards.

- Please outline the measures taken to reform Egypt's Counter-Terrorism Law to ensure its adherence to the principle of legal certainty and to avoid its broad misuse for acts that are not inherently terrorism-related.

- Please provide information on any additional amendments to the legislation mentioned above.

- Please clarify the measures your Excellency’s government took to review the proposed amendments to the Egyptian Criminal Procedure Law in light of the abovementioned observations.

For the original and full version in English: